Mary Olney Brown and her sister Emily had come with the Oregon Trail. They’d prepared for this opportunity since the moment they arrived. Being in their mid-late twenties at the time of the Seneca Falls Convention and the start of the movement in 1848, they had both nurtured the hope that they were called upon to mold the shapeless frontier. Washington Territory would integrate the enfranchisement of women, it’s fabric embelished by the sister’s shared passion and tenacity. While Mary had mastery of the arguments and had what was considered to be “more than ordinary intellectual endowments”, Emily had the greater success of the two in persuading men that she was no threat to them. The amendments to the Constitution ushered in by Reconstruction ignited their debate. Just as newly freed, black men were afforded the full rights of citizenship, women too were fforded the same claim by the same language. Set in perpetuity by the fourteenth amendment.

In 1870, a minor revision had passed the Territorial legislature. By simply removing the word “he” from the description of citizen, the assembly laid the field open for the suffragist sisters to harvest. Mary’s confidence was sure and her arguments were sound. No reasonable debate could result in any other outcome than the women be allowed to vote. Her remarks, however, whether read from the page or spoken aloud, wounded the ego like a cleaver.

It was of no surprise when word reached Mary of her sister’s success. Emily and her partners at the poll had disarmed the attendents in Grand Mound, a tiny district outside of town. They layed out a picnic and invited the officiants to partake of food while engaging them in a casual discussion of why it was just and fair to allow women to vote. They posed no harm, but rather hoped to influence politics for the betterment of all. Their ballots were received and the word was carried on horseback to the neighboring district of Black River, where more eager women waited. The women were voting. The heralding angel declared a miracle had taken place and that the same was possible elsewhere. In Black River, more ballots were cast without obstruction. While Emily and her cohort were enjoying the exercise of their political rights, Mary Olney Brown and the women of Olympia were “suffering the vexation of disappointment.”

The day before the election the judges [in Olympia] were interviewed as to whether they would take the votes of the women. They replied ‘yes, we shall be obliged to take them. The law gives them the right to vote, and we cannot refuse.’ The decision was heralded all over the city, and women felt as if their Millennium had come. Before 9 the next morning, the word had been communicated all over town that ‘the women need not come out to the polls as the judges would not take their votes.’ They would give no reason why.

More often than not, the vice industries had something to do with a flip of this nature. The liquor, gaming and tobacco men predicted that when women vote, they will opt to drive them out of town in favor of promoting temperance. Campaigning on the promise to rid politics of corruption from every angle, the women left them little choice. True womanhood, after all, was humanity’s moral compass. If she were given authority in politics, their days in the unregulated western sun were numbered.

Suffrage became emblematic of a war on two fronts. On one, the suffragist threatened the natural order. On the other, she sought to correct for man’s more base and destructive instincts. Mary and her compatriots of Olympia met together in preparation for the battle on election day.

About a dozen of us gathered together, finding most of them inclined to back out. I urged the necessity of our making an effort. It was best not to give up as the rest had done. If we did it it would be harder to make an effort next time; that I had been to the polls once and had my vote refused, and could be refused again. At any rate, I had the right to vote. And I should go and offer it if I had to go alone. 3 of the number said they would go with me Mrs. Patterson, Mrs. Wylie and Mrs. Dofflemyer; these, with Mr. Patterson, my husband and myself made up our party.

***

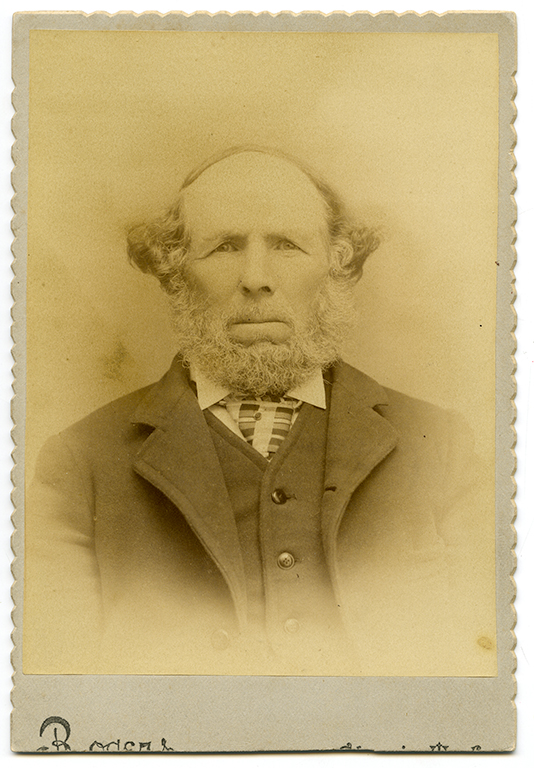

The route to the courthouse was lined with familiars, conveying a mixture of support and disgust. Mr. Brown had taunts directed at him from men in the community. That if he let his wife attempt to vote, she would be ridiculed and verbally assaulted. How could he allow her subject them both to public ridicule? He sincerely believed that he could not stand in Mary’s way, even if he wanted to. Benjamin Franklin Brown had been married to his wife for forty-three years. They’d had eleven children, six of whom had died. He was a farmer who loved and respected his wife as his equal. This was not a sentiment shared by many married men at the time.

When they arrived at the courthouse where the election was being held, Isaac Dofflemyer waited, anticipating his wife was among them. He moved assertively forward to claim his wife. Susan Dofflemyer hesitated before bowing in defeat and, without a word to Mary or the rest, followed meekly behind him. The price for her insubordination was likely greater than the satisfaction she might feel in casting her ballot.

A cart rattled to a stop in front of the courthouse. The open rear compartment contained a man so drunk, he couldn’t manage to remove himself independently. After he hollered out for assistance, he was hoisted to a stand by two men who put a ticket in his hand and delivered him to place it in the ballot box. His vote was received. As he sauntered back toward the carriage, a shade of pale suprise arrested his face and he collapsed forward, expelling foul fluids into the street.

The display was a farce. A mocking effort to flaunt male suffrage in the faces of any self-righteous haag who dared attempt to vote. As the man rolled himself back into the cart, Mary felt compelled to use the comparison of qualifying character to her advantage. She moved briskly to the table and extended her arm out, ballot in hand.

“We have decided not to take the votes of women”, one of the men declared without inflextion.

“On what grounds?” Mary mirrored flatly. Her arm still outstretched.

There was no answer. They simply sat and stared past her in resolute defiance of her presence there.

“Under the election law of this territory I have the right to vote in this election – have you the election law by you?”

“No we have not got it here.” Another of the men inserted coldly, staring beyond Mrs. Brown at her companions and the onlookers that began to accumulate around them.

“Under this territorial law,” Mary had prepared for this, her voice elevated so as to educate any within earshot, “I claim my right and again I offer you my vote as an American citizen. If you doubt my citizenship, I will insist on taking the oath – Right here and now.”

There was silence. “Will you receive it?”

“No. We have decided not to take women’s votes and we cannot take yours.” The injustice clawed into her, causing her voice to deepen and boom with rehearsed rage.

“Then it amounts to this.” She turned now to address the modest crowd, “The law gives women the right to vote in the territory, and these three have been appointed to receive our votes. They sit here and arbitrarily refused to receive them, giving no reason why only that they decided. There is no law to sustain this usurpation of power. We claim legal redress – “ Mary returned her ire to the three seated with their arms folded and faces blank. “Are you willing to stand a legal prosecution?”

“Yes.” They each declared in staggered unison. One after another, each member of the party were unceremoniously denied, save the two men among them.

Mary returned home resolute. A shift in strategy was required. She crafted a statement, eager to reignite the passions of her fellow Olympia women to push on. She wrote petitions as President of the Washington Territorial Woman Suffrage Association but could not get a single member to circulate them in town. Everyday, Mary set out on her way to fullfil her ordinary errands and canvassed everywhere she happened to be.

“My experience taught me that the principle opposition to womans voting came from ignorance as to her true position under the government. She had come to be looked upon almost as a foreign element in our own nation, having no lot nor part with the male citizen.”

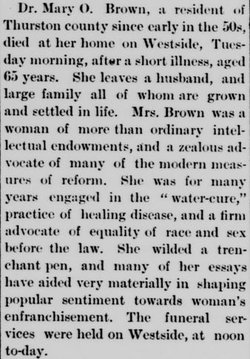

Mary Olney Brown’s written accounts of her experiences gained her notoriety within national movement, immortalized in the pages of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s History of Woman’s Suffrage in the United States. Mary had accompanied Susan B. Anthony on her travels through the region in the fall of 1871, witnessing the cause be dealt blow after blow. The experience of permanent suffrage in the state was just 15 years outside of her mortal reach. But as she was a writer. Her legacy as part of the movement has secured her place in the story. Her description of events expressed the opposition that few had the fortitude or position to continually resist. Notably, she had the support of a marriage and the devotion of a husband that gave her a security not often experienced in her time.

***

Sources:

Lane Morgan, “Charlotte Emily Olney French casts the first vote by a woman in a Washington Territorial election at Grand Mound in Thurston County on June 6, 1870.”https://www.historylink.org/File/20717

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan Brownell Anthony, History of Woman Suffrage: 1876-1885, Vol. 3, ed.