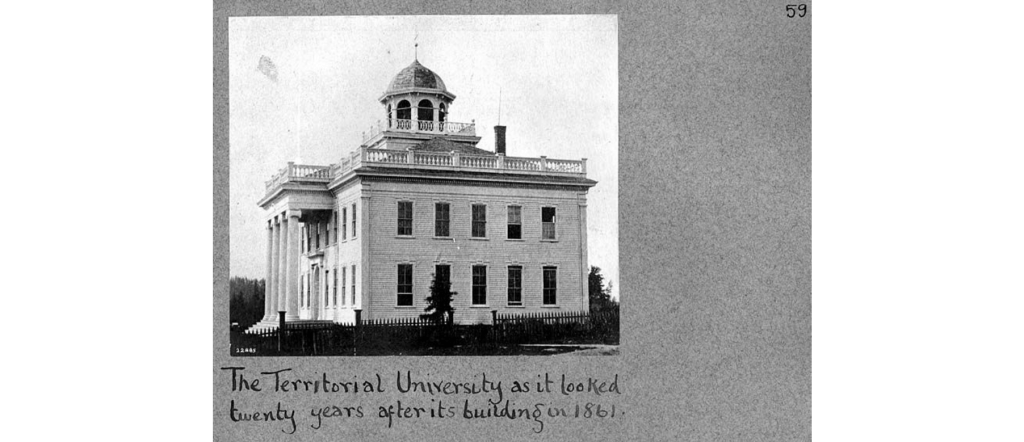

The University was stately, rivaling the Territorial Capital building in Olympia – which cost just as much to build. The early leaders of Seattle elected to house the University in place of the territory’s capital – believing enlightenment to offer greater yields than government. Arthur Denny gifted the Territory with the land to build it on. Now situated in Seattle’s burgeoning downtown, it served as the emblem of the city’s aspirations.

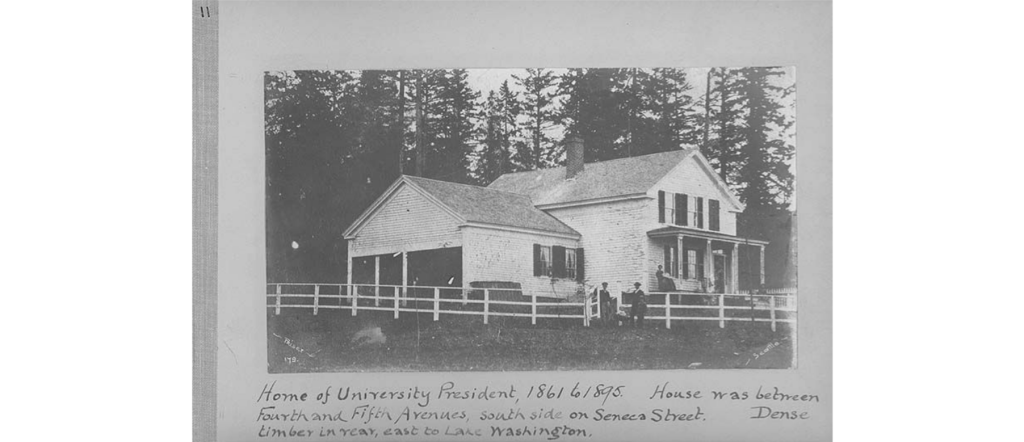

Agnes resided in the University President’s house on Denny’s Knoll. Professor Eugene K. Hill, his wife Jeanette lived there, along with the Scottish mother-in-law who served as the dormitory’s chaperone. The Hills had no children of their own and assumed a surrogate role for Agnes while she lived there, nurturing her ambitions.

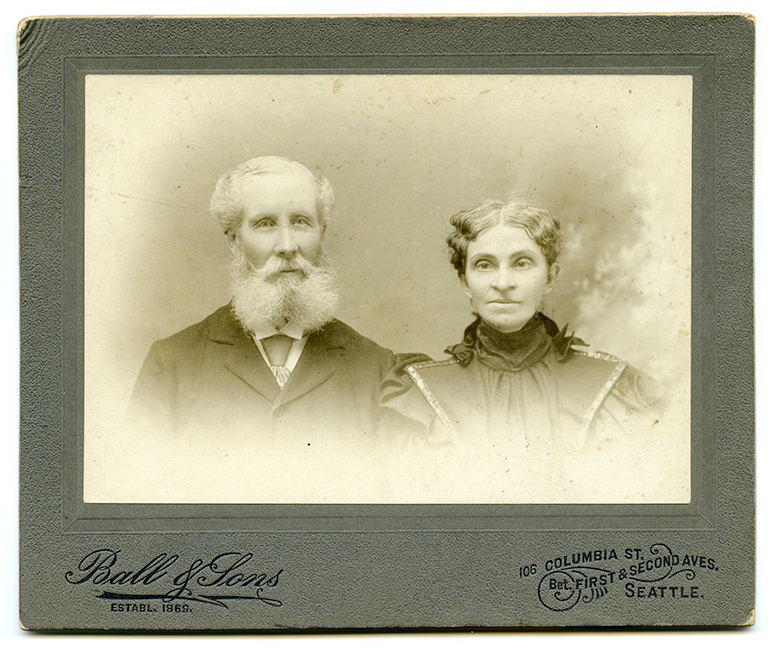

Eugene Hill was a mathematician, soft-spoken, and not fond of the business side of running a university. He was tall with a long face and beard. He had a kind countenance and undersized, smiling eyes that were disarming and warm. His wife Jeanette, or Nettie, by contrast, had striking and broad features with intense, commanding eyes. She was gifted in Latin and Greek and dutifully taught those subjects while also serving as her husband’s administrative assistant. They were a true partnership, eager to improve the primitive conditions they found when they arrived.

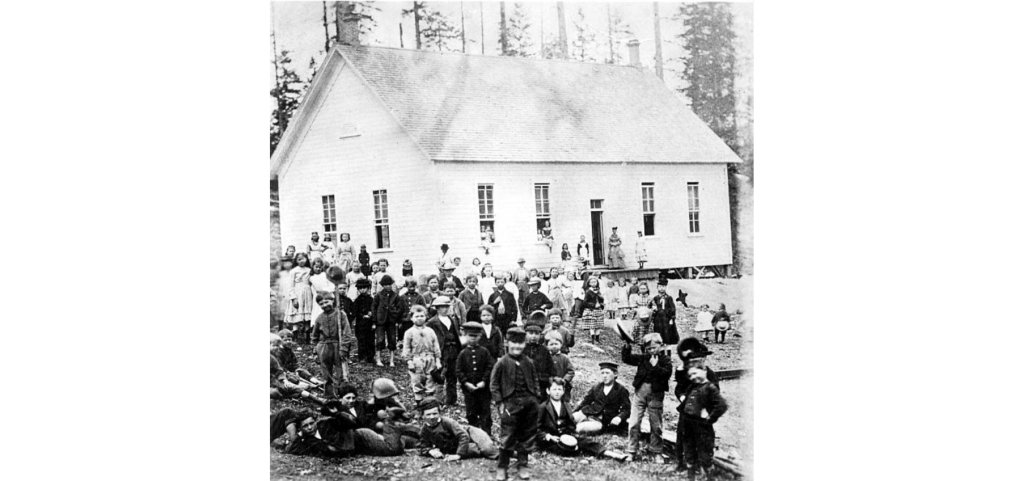

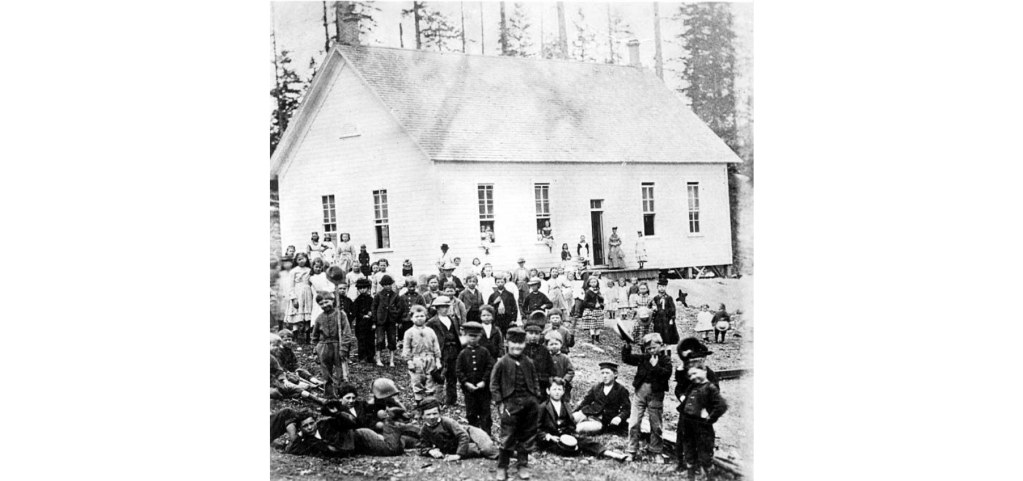

With the institutions of the settlement taking shape, young Agnes emerged on the scene of the university still in its infancy – eager to stake her own claim. She established the school’s first student publication, with herself as editor, though no evidence of the paper still exists.[1] In those early days, admittance to the Territorial University was not limited to those seeking higher education. Funding flowed from land sales and tuition, leaving the Hills to allocate most of their energy to market the school’s merits and entice prospective students. With each year threatening to be the University’s last, they scrambled each term to keep the doors open. They had to expand and educate primary school children and “Large Boys”, as Nettie Hill called them; illiterate adults who were too embarrassed to be seen learning to read and write alongside children in the common schools.[2] Anyone who wished to matriculate was able unless they were a native or half-breed, as laws protecting the fundamental rights of citizens did not apply to them.

A teacher’s convention, the first of its kind in the territory, was held in August of 1872, assembling the most influential educators from throughout the pacific northwest region and British Columbia. The Hill’s invited Agnes to participate, lending her musical talents to the event. She led hymns and played interlude music for each session. A chorus of educators sang together, cheerfully consecrating the work with divine purpose. Agnes was positioned in the hall where the very first standardized improvements to public education were proposed and discussed. High schools for the instruction of collegiate and professional studies, a five-day school week, and debates about all manner of topics ranging from the need for compulsory writing to the merits of arithmetic for primary-aged students.[3]

***

Captain Charles Winsor, cousin to Agnes’s father Captain George Winsor, was slated to pilot a ship bound for Seattle in 1866. Part of Asa Mercer’s second voyage of the infamous “Mercer’s Belles” expedition. Charles had likely agreed see to Agnes’s safe passage and help her get established ahead of the rest of the family. At the age of twelve, Agnes left home upon a descendant of her own family’s shipbuilding legacy. Together with the Captain, Aunt Mary, and cousin Minnie, the party boarded the S.S. Continental; a member of the Winsor’s Clipper fleet.

No respectable women would sail on The Continental, one Boston newspaper scolded; slander introduced to prevent further migration of Massachusetts’ daughters to the west. Gainful employment and land for themselves was ultimately worth the risk for some. Far more lucrative than the fall from social grace could ever quantify. To an enterprising young woman whose notions of romantic marriage were just another casualty of war, Washington existed on an alternate timeline. A land of untamed potential that sought them out, eager to surrender to a woman’s influence. Adventure and prosperity awaited them.

In the Plymouth town of Duxbury, Massachusetts, the Winsor family had built their legacy in manufacturing ships. The venture made several of the town’s founding families very rich. Since the emergence of the Clipper and its overwhelming popularity, the nearby ports of Boston were better suited to the task of production, and Duxbury had to rely on its seaside charm to stay solvent. Mariners like George were marooned long before the civil war began. He could not compete with valor-thirsty sailors whose legs didn’t buckle under the weight of the years at sea. George had at one time looked the part of a Winsor. Captain of his own ship with his first wife, Alice, and their six children growing up onshore.

After much time saving what he’d earned, he had bought a 20-acre parcel of land. More time passed before he could secure enough to build the home befitting his longsuffering wife and family, but not without the need to borrow a large sum from Seth Sprague of the Sprague shipbuilding family. An ornate, Greek revival style cape with room for his children, now nearly grown, with the earnest hope they might return with children of their own. Alice died suddenly, followed soon after by their daughter Almira not long after the home’s completion. Ruin charted a new path from Plymouth, and at 58, George left again in search of a livelihood as a traveling salesman. He returned to from New York to Duxbury with a new bride, Francis Cornish Winsor, who was just 33 – a hardworking, modern and staunchly religious woman who harbored ideations of women’s suffrage. In 1850, a daughter, Wilhelmina, was born in the grand home her father had built, now absent of the family that preceded her. Soon after, the three were relegated to a more modest home in South Duxbury after George was forced to sell the estate. Born into relative obscurity, Agnes was born in 1855.

The brave, youngest Winsor daughter left everything for a promise that waited for her in the Sunset Land. From Rio de Janeiro to the Straights of Magellan and the Galapagos Islands – San Francisco was a welcome sight on the other side of the world. One more ship would ferry them north to Seattle and their journey’s end. When women made their debut in these rough settlements along the sound, they were in a state of shock by what they had found;

“Dusty streets without sidewalks, non-existent or inadequate schools, piles of garbage with their attendant flies and rats, inadequate Water and Sewer systems, dilapidated buildings, transient populations, and towns where saloons outnumbered other types of social amenities and men outnumbered women.”[4]

The social lives of young people were complicated by sporadic settlements, dispersed along the Sound and isolated by dense forest. The resilience of youth and the limited number of female partners demanded that great lengths be gone to to bring them together. Steamers that made up what was known as “the mosquito fleet” made whistle stops to all the major ports, extracting and delivering young women to where the dances were held. Though a seemingly intimate backdrop for making romantic connections, the market for partners was alarmingly limited.

The surface of Lake Union had frozen to roughly 6 inches the winter of 1872. Young men from the University emptied out onto the ice. Young women that were willing to abandon grace, slid to meet their counterparts toward the center of the 580 acre body of water. Hindered by the fabric that dragged like a fallen parachute around them and stifled their flight. Ordinarily an arena for commerce, Lake Union hosted pods of seagulls and a ballet of wooden vessels, ferrying lumber from Lake Washington to the Puget Sound. Now seized by uncharacteristically cold temperatures, the Lake was commandeered by the young who were starved for frivolity. Agnes was seventeen and independent, teaching primary school children at the University.

“Winter term will open on the 27th under the Presidency of Professor E.K. Hill” the Puget Sound Dispatch announced in September, “formerly of Michigan University, who as a practical teacher has won a high reputation in the profession.”[5] The university moved downtown, centrally located on Fourth and University to attract more interest and resemble more closely what the Hills had become accustomed to. They invested in special ordered seats and “gothic” desks from Chicago, updating the facilities with modern appliances. They added student housing furnished with blackboards, window shades, hard finished walls and matting on clean floors. They promised prospective students from anywhere they might be in the country, to note that the tuition had been reduced by one-third and there would be no need for “required, unnecessary texts.” The Hill’s were determined that Washington’s University would rival any of those they had observed in the midwestern states. Gambling on upgrades in order to make, what they believed to be, investments in their future legacy.

Despite their efforts, Eugene and Jeanette Hill were failing to attain fiscal legitimacy for the University. Whether as an expression of their personal values or as a desperate attempt to secure the institution, the Hills invited a scandal that amplified the community’s bigotry and scrutiny of their leadership.

“Bitter complaint has been made to the Regents of the University against Professor Hill for admitting colored children into the school, and one parent – a very ardent and active Republican politician- has taken his own children out of the school on that account.”[6]

The theoretical question of civil rights had been answered several years before. Access to education ought to have been resolved by the Civil Rights Act of 1866, declaring all naturalized persons, regardless of race, citizens – with all rights and privileges of citizenship restored to them. Despite the University’s status as a public institution of higher education, the law of the land was once again undone by public opinion. Prof. Eugene Hill was dismissed;

“We are reluctantly compelled to discharge with the valuable services of the President, Professor E.K. Hill, for the term which commenced today” the Dispatch reported, “This is done without prejudice to the character of the Professor, he bears with him from the field of labor the high regard of all with whom he has been associated, as an accomplished educator and exemplary Christian gentleman.”[7]

The Hill’s boarded a boat to San Francisco. Eugene had been offered a principalship at a private school for girls in California. How Agnes regarded the decision to invite inclusion into the University isn’t clear. But their dismissal and absence were significant.

***

Public schools were beginning to feel the strain under the city’s rapid growth. News that the Northern Pacific Rail would place its western terminus in Tacoma, forty miles south, had a rippling influence. The Railroad was a “king maker” and despite the lack of economic growth and opportunity, the rate of migration to the city was significant – the population of school age children alone grew from several dozen eligible pupils in one school to more than 400 by 1874, requiring at least two more schools be built.

Seattle’s North School was one of three public schools serving a student population of 480. North School, built on 3rd Ave and Pine Street, had two rooms to hold all the students that lived north of Cherry Street. Agnes, with Miss Lizzie Clayton, had accepted a joint principalship of North school awarded by Professor Hall, who headed up University prior to the Hill’s arrival. The youngest brother of Professor Hall was killed in a violent accident on the docks, marking his exit from education until 1874.[8] Hall was now superintendent in charge of Seattle Public Schools, while also being considered to head the expansion of Northern Pacific Railroad into Seattle. So highly regarded, it was expected that he could negotiate both tasks simultaneously, better than any other could accomplish them alone. Hall was egalitarian in his approach, expanding the scope of public education to include night school at the Central campus to better accommodate any who were interested in learning. Courses were offered at a low cost, which could be awarded back for exemplary performance.[9] Agnes was the recipient of one such prize, the award for best specimen in penmanship.

Professor Hall kept exceptionally high standards. He saw the opportunity of new schools and recent growth to require a greater degree of discipline from teachers. Capitalizing on the spelling bee craze that settled on Seattle in the spring of 1875, he ignited competition among the young scholars. An arena in which Agnes proved to be a fierce competitor.

“The contestants dropped out one by one until Miss Nellie Terry and Mr. Levy, on opposite sides, were the only two left. Mr. Levy finally was declared the victor, Miss Terry having missed a word. A match was then gotten up between the ladies and gentlemen. The sides were soon reduced to Miss [Agnes] Winsor on one side, and Mr. Levy and our reporter on the other. All missed a word and all were given another chance. We then dropped out and after listening to the contest between Miss Winsor and Mr. Levy for some time, we left with neither down. We did not hear how the match terminated.”[10]

Seemingly sore in their loss and neglectful in their coverage of the event, the reporter either truly didn’t care to learn who had won, or the victor was not who he desired to have bested him. With the conclusion unresolved, the portrait it paints is enough.

More than intellect and accomplishment, Mr. Hall desired sacrifice. Discipline in the form of obedience. Along with other school officials, the Superintendent banned all young teachers (most of them young women) from attending dances and skating rinks. Believing that “the practice of staying up late at night tends to incapacitate the teachers for proper attention to their pupils the next day.”[11] This formal declaration was met with outrage. Young women and men required a world outside the drudgery of attending to the motley mass of children that weren’t their own, clinging to what remained of the day and the possibilities it held. Remembering the rich societies, they left behind in the east before they arrived in a landscape that was growing more hostile to the innocent desires of young people. Agnes left her position in Seattle schools. In Seabeck, no such restrictions inhibited young women from finding love, friendship and enjoying music and conversation in the company of strangers.

[1] Agnes Winsor Prather Obituary, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/48365546/agnes-prather

[2] Jeanette Hill reminiscence of early days at the University of Washington, approximately 1872-1899. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, PNW00432.

[3] “Teacher’s Institute” Puget Sound Dispatch, August 28, 1873

[4] Sandra Haarsager, Organized Womanhood; Cultural Politics in the Pacific Northwest, 1840-1920, University of Oklahoma Press, p. 180

[5] “The University” PSD, Vol 1, Num 41, September 5, 1872

[6] “Civil Rights” PSD, Volume 3, Number 7, 29 January 1874

[7] “The University School” PSD, March 12, 1874

[8] “Fearful Accident” PSD, June 6, 1872

[9] Angie Burt Bowden, Early Seattle Schools of Washington Territory. Lowman and Hanford Company (Seattle, Wash.), 1935, p 194.

[10] “Spelling School” PSD, 13 May 1875, Thu · Page 3

[11] Bowden, Early Seattle Schools

One response to “Miss Winsor”

Very nice story. Well written and easy to follow.

LikeLike