“He has usurped the prerogative of Jehovah himself, claiming it as his right to assign for her a sphere of action, when that belongs to her conscience and her God.“

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, The Declaration of Sentiments

“Ida Clare” was one of Lelia Robinson’s chosen pseudonyms. Used for her weekly columns on Boston society, published in lesser known rural papers. [2] Robinson began writing at the age of twenty-one for The Times, The Post and The Globe. For less reputable publications like the Fall River Daily News, Robinson wrote under nom de plumes like “Trimontaine” – a name derived from original Puritan settlers that named the tri-peaked peninsula of Massachusetts’s; the site of their home in the new world.

Historianne feels that way to me. Not that I wish to shield my identity from work I’m less proud of. Even though I write about people and times before my own, the work is deeply personal. I hope to remove myself from it, to a degree. At times, these histories feel very familiar. Not in the reincarnated sense. The way that literature can feel. When a story hones in on what is so universally human. I was asked in an interview recently, what draws me to a particular history. While I tend to gravitate to women’s stories, given my own experience, it’s not their accomplishments in the face of adversity that interests me. It has more to do with the injustices and threads of moral ambiguity.

I have found many examples of this in the course of my research, but one court case, the women involved, and the impacts of its outcome are the subject of the work I will present at the Pacific Northwest Historians Guild Conference in September, 2023. One of the three women I feature, Lelia Josephine Robinson, was “Bostons’s Woman Lawyer” who made her way to Seattle in the early 1880’s. She would have taken issue with being referred to as a woman-lawyer;

“Do not take sex into the practice. Don’t be ‘lady lawyers.’ Simply be lawyers, and recognize no distinction … Let no one regard you as a curiosity or a rara avis. Compel recognition of your ability.”

Lelia J. Robinson, 1887

Lelia came from a middle-class family and was educated in Boston public schools. She married a tinsmith from Nova Scotia named Rupert Chute in 1866, when she was sixteen. They had a daughter in 1870, Lily Pearl, who died of cholera at four months old.[3] Lelia escaped into journalism, then sued for divorce in 1878 on the grounds of infidelity; a suit that she won and a period of her life that she would never again mention in her extensive writings.

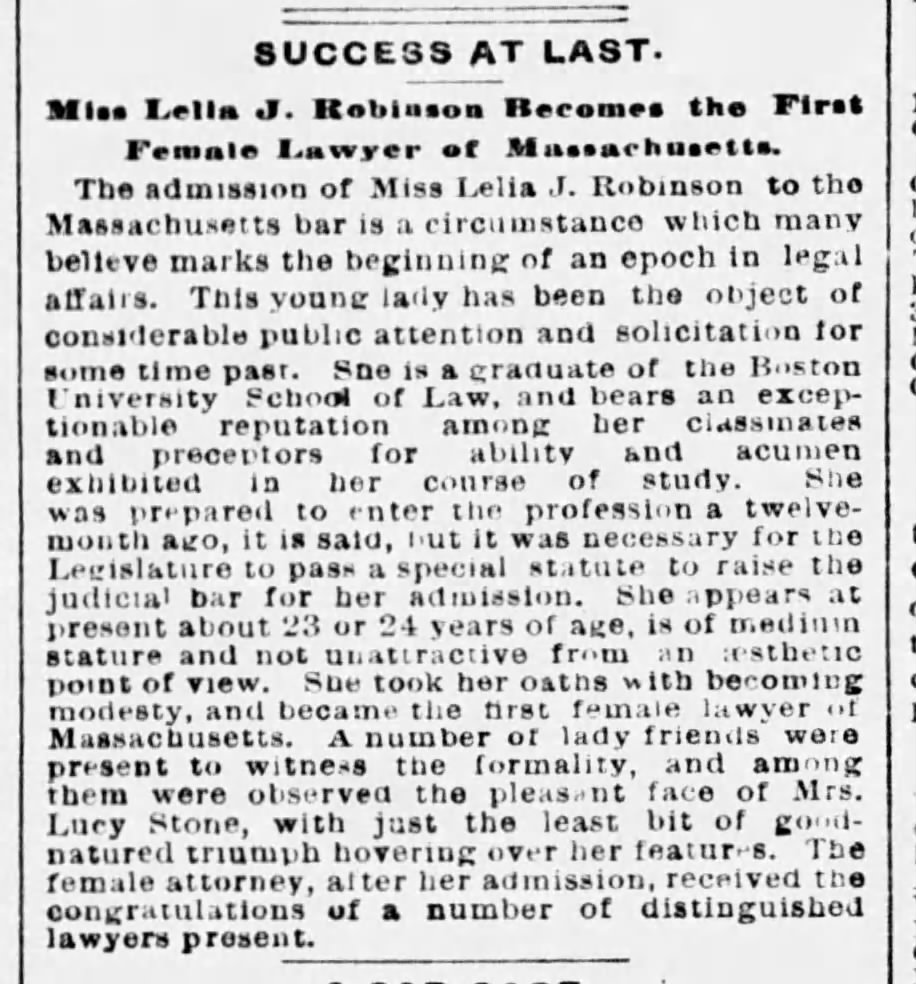

She immediately entered Boston University Law School. Two other women had attended before her, though neither of them finished. Her initial reception was cold, but not overtly hostile. When asked where she was to sit for a lecture, she was told to “sit anywhere”, only to learn that the seat she selected belonged to someone whose name began with C. The room was organized alphabetically. The fellow whom she supplanted was too polite to correct her, and there she remained. It was a far cry from the taunts and growls that threatened the women that came before her. Instead “[They] seemed puzzled to understand why a woman should want to study law.”[4] In 1881, Lelia J. Robinson graduated fourth in her class and set her sights on obtaining a law practice.

To apply to the bar in Massachusetts, all one had to be was twenty-one years of age, a citizen o the common-wealth, a someone of good moral character. Once criteria was met, applicants submitted to an examination. Despite having just graduated with honors, her bid to be examined was denied. She took her case to court.

“Robinson’s brief argues that the term ‘citizen’ included women, that it was a sex-neutral term, and that she should be examined. She also argued that in withholding the opportunity to take the bar exam, the state was abridging privileges and immunities guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment.”[5]

The State Supreme Court disagreed. Undeterred, she spoke to groups of people in libraries and even addressed the Massachusetts state legislature, where she evoked a departure from the “old-established order of things” while consoling that her admission would be only “an experiment.” Assuring the legislative body that women “would limit themselves to appropriate areas of the profession and know their place in society.”[6]

A bill was passed allowing women to take the bar examination. Lelia Robinson becomes the first woman to take and pass the Massachusetts state bar exam. This, however, was not the end of her struggles to practice law. For three years she waited. What work she did find was neither challenging nor rewarding enough to keep her in Boston. The Washington Territorial Legislature had recently liberated women from common law.

Adherents to common, or natural law, believed that in both country and home, the man is sovereign. That upon marriage, a woman forfeits her identity in exchange for the protection of marriage. Washington voted to replace common with community law – declaring that, in regard to property, the married woman has equal claim and authority over the household. This yield in property rights gave way to a broader interpretation of citizenship. As equal domestic partners and co-heads of household, women were granted the rights and privileges of full citizenship in 1882. Lelia Robinson became one of many to leave home and family behind, to explore the potential of the farthest frontier.

“In May of 1884, I arrived in Seattle, Washington Territory, the last stage of a two-months, transcontinental trip, full of curiosity concerning many things in the life of that far, new western civilization, but with a more eager interest, naturally enough, on the ‘woman question’ than any other.”[7]

To be continued …

[1] Elizabeth Cady Stanton, The Declaration of Sentiments, 1848.

[2] “Argus and Patriot”, Montpelier, Vermont, Wed, Jan 21, 1885 , p. 4.

[3] “Massachusetts State Vital Records, 1841-1925”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:N7KZ-8HM), 13 December 2022.

[4] Mary A. Greene to Equity Club Members, “Mrs. Leila Robinson Sawtelle” 5 April, 1888, p. 51

[5] Jill Norgren, Rebels at the Bar: The fascinating and forgotten stories of America’s first women lawyers, (New York University Press, 2013) p.159.

[6] Rebels, p.162.

[7] Robinson, L. J. (1887). Women jurors. Chicago Law Times, 1(1), p. 22.