Olympia, Washington – 1905

A brown bear was captive in Mr. Brown’s Curiosity Shop on Sixth Street in Olympia, Washington. A cub, trained to roll over and stand on his hind legs to the delight of the customers. The bear made frequent attempts to escape, despite Mr. Brown’s best efforts to civilize and seduce it with creature comforts. To prevent this, Mr. Brown used a piece of gas pipe to bludgeon the creature to death. He gutted and stuffed the bruin hide to resemble many of the other ornaments that adorned his collection. Mr. Brown could not allow the creature to upset the calm the people had become accustomed to. Customers would come in turn to look upon and remember the bear as it once was, posed upright with an expectant expression. Awe-inspiring and obedient.[1]

Objects of exotic, untamed origins were a growing fascination at the turn of the century. Exhibitions of the grotesque, native or abnormal were traveling the country; vaudeville, circus shows, or immortalized in print, the spectacle of “the other” managed to both captivate and threaten simultaneously. Such was the ongoing fascination with the insane. While civility demanded the application of moral treatment, the indigent poor, infirm, disabled, and mentally ill were to be segregated from the whole.

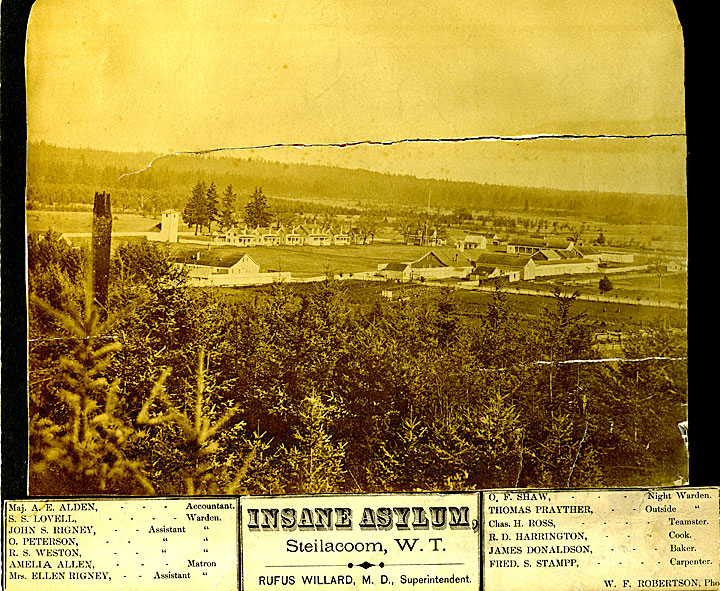

“The asylum for the insane at Steilacoom needs to have a cleaning out of officials from superintendent and matron down, if half of the reports be true as to the manner in which it is conducted.” Salacious tales of women with their toes eaten by rats and a young black man being kicked to death stirred outrage among well-intentioned citizens.[2] The head matron, Mrs. Charles Herman, resigned in June. Business as usual resumed at the asylum. No smoke, no fire.

Mrs. Thomas Prather had scarcely been matron a year before an incident drove her to render her own resignation thirty years before. Agnes Winsor, as she was known then, was twenty-three when she accepted the position. She was well educated at the Territorial University (University of Washington in its infancy). She was editor of the first student newspaper and went on the teach in Seattle at fifteen.[3] She was offered a principalship of her very own school when Dr. Rufus Willard, Superintendent of the Asylum for the Insane at Steilacoom, sought her out. He believed the position required “swo many good qualities of the head and heart,” all of which she possessed; “cheerful, industrious, watchful, conscientious, self-respecting, and respectful towards others.”[4] Agnes accepted.

Steilacoom, W.T. – 1878

The grounds were in a state of improvement upon Agnes’s arrival. The fact that the hospital had once been a military installation was still apparent. Barracks had become wards, officers’ housing now housed contractors, staff, and the attending physician; tasked with the care and keeping of the insane. The hospital’s head matron, Ms. Mary Rennels, took Agnes and her things to their residence at the far end of Officer’s row.

Agnes observed Ms. Runnels’ model of care for the various patients. The were eighteen women housed in the asylum and relative to the main population, there were only seven women that posed no threat. Agnes’ primary responsibility was to provide treatment to the eleven others segregated on the opposite end of the complex in the Female Ward.

“I never struck Mrs. Moore intentionally” Mary Rennels objected, “except when Mrs. Moore would come at me to fight me, I would push her off.” Rennels defended herself before the state’s investigator, who took dictation of her testimony. Mrs. Moore was an immigrant from Scotland, wife to a farmer and mother to six children. The nature of their apparent rivalry was mutual and strange. “[She] would attempt to strike us or pull our hair nearly every day, we only used force enough to defend ourselves.”[5]

While the commitment ratio of men to women was often 3:1, married women made a disproportionate dent in admissions. It was not uncommon for women to be committed at the request of their husbands for “domestic troubles.” Epilepsy or menopause, obscene language, mourning a death for a length of time deemed excessive by friends or family. Clinging to radical religious beliefs or for speaking too assertively about unpopular beliefs; commitment was a means to silence and discredit women before the whole community. [6]

“When I first went there, I at first thought [Mary Runnels] was unnecessarily rough but soon found I was mistaken.” Agnes recalled after having left her position at the asylum.

“It is sometimes necessary to be a little rough in administering medicine and in self-defense … Force from the patients is always to be looked for, but you can never tell when it will occur. They get very violent sometimes. As a usual thing, there is more injustice to the matrons attempting to be kind to the patients than there was done to the patients by the matrons in repelling the attacks.”[7]

Mrs. Washauer had been subjected to the standard routine. Wardens strapped her to bed when she had refused to go to sleep of her own accord. The matrons stood by to supervise. Agnes returned to Mrs. Washauer’s bedside the following morning. She removed the restraints as she had done dozens of times; first from the wrists and then the ankles. Each belt unclasped, each taught leather strap slipped free, she moved gradually away from the patient and closer to the door. Once liberated, Mrs. Washauer seized Agnes by the hair, pulled much of it out and commenced kicking to kick her and tear at her dress. Agnes was laid up for three weeks.[8] Fearing for her safety, she resigned as matron and agreed to be governess to Dr. Willard three young children. Thomas Prather had been Outside Warden for three years at the asylum. Following Agnes’s exit, he offered himself to her as partner and protector. They were married there, at the home of Dr. Rufus Willard the following September.[9]

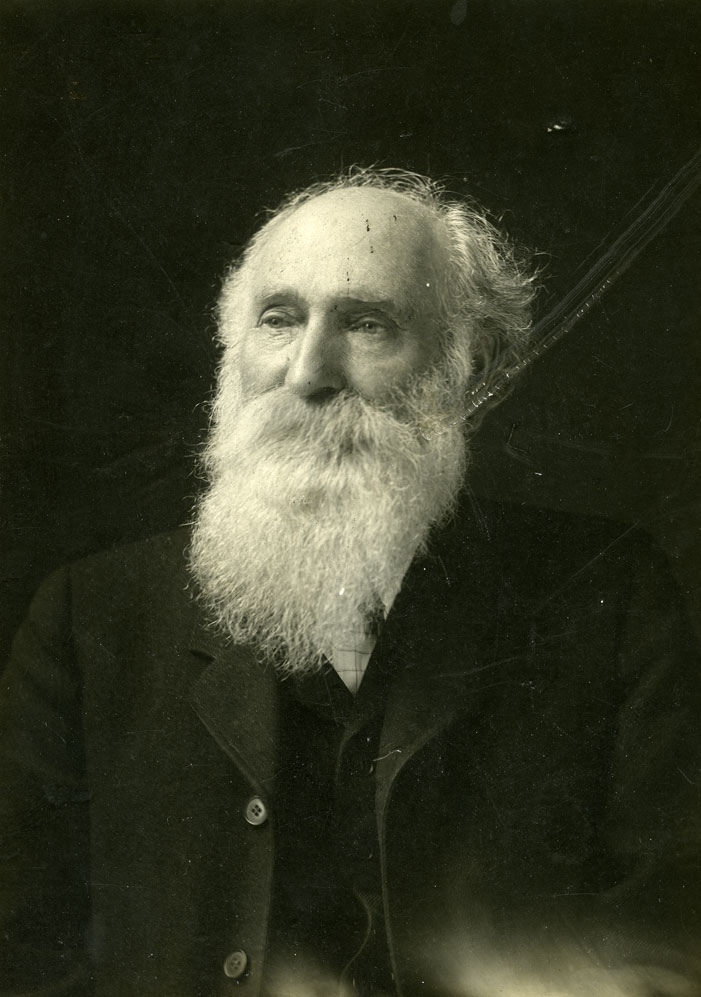

The Prather’s called Olympia home. Agnes had three children, two of whom survived to adulthood. She was a Suffragist who voted and served on juries before their efforts were undone in 1887. Thomas Prather, a well- regarded pioneer of Olympia, served three terms as Commissioner of Thurston County. Twenty years go by with no mention of Agnes.

Then in August, 1906;

“Mrs. Agnes Prather was committed Monday to the Steilacoom Hospital for the Insane, on a charge of insanity, made by the prosecuting attorney P.M. Troy.” Agnes, once believed to be a woman of talent and intellect, had become a spectacle. Victim of melancholic hysteria. Ridiculed with language that betrayed disgust. Described as a bearded woman in grotesque garb, startling people on the street. Agnes Winsor Prather was condemned to the very asylum that frightened her into temporal protection that only a marriage could secure.

“Her husband, Thomas Prather, has the sincere sympathy of our people. He has been indefatigable in his efforts to keep her within doors, but it was impossible to do so. She will be well-cared for in the asylum, and our fair city will be relieved of a palpable persistent misfortune, liable at any time to lead to trouble and loss.”[10]

Thomas Prather began living with a woman named Margaret Rose who aided in raising Agnes’s young son to adulthood. In 1918, Thomas Prather collapsed suddenly and died outside the Knox hotel where he had been lodging. Agnes was released three days later. Despite laws that required patients be returned to the community as soon as feasible, Thomas Prather had paid to keep his wife sequestered and silent for thirteen years. [11]

“Where are her friends?” bystanders questioned as they witnessed Mrs. Prather’s public decline.[12] She was said to have approached strangers to ask if they would procure laudanum for her. She reportedly sought out the druggist to determine how much was necessary to kill someone.[13] Whether the intended someone was herself or her husband, Thomas Prather, is unknown.

[1] The Washington Standard (Olympia, Washington), 08 May 1903, p 3.

[2] Lue F. Vernon, “Driftwood; Individual Opinion” The Washington Standard, 22 Dec 1905, p 3

[3] “Mrs. Thomas R. Prather” The Washington Standard, 31 Jan 1919, p 8.

[4] Report of the Superintendent of the Hospital for the Insane (Elisha P. Ferry Papers), August 16, 1877-August 15,1978, p 24.

[5] Elisha P. Ferry Papers, Box 1K-1-4, Insane Asylum; Inspections and Investigations, Washington State Archives Research Room, Olympia, p.

[6] Katherine Pouba and Ashley Tianen, “Lunacy in the 19th Century: Women’s Admission to Asylums in United States of America” The Oshkosh Scholar (University of Wisconsin), Vol. 1, April 2006, pp 95-103.

[7] Inspections and Investigations, pp. 73-78

[8] Inspections and Investigations, p. 82. Based on testimony taken from matron, Serepta Herrington. No details involving the incident with Agnes Winsor has been found.

[9] “Married” The Washington Standard, Sep 05, 1879, p 5.

[10] “An Unfortunate Presumption” Washington Standard, August 31, 1906

[11] Warren Fanshier, History: Western State Hospital, January 2, 1976, p 4.

[12] “An Unfortunate Presumption” ibid

[13] “Committed to Hospital: Mrs. Prather Pioneer”, The Morning Olympian, August 28, 1906, p 1.