Mrs. Emma Taylor was a seamstress in Seattle before she became the city’s first Police Matron. Taylor was her married name. The surname that once described her origins in Devon, England, was Hayman. Similarly apt for her father’s occupation as a farmer. She came with her younger brother, William, to the states aboard the ship where she likely met her husband, Thomas Taylor. The two were married in Wisconsin on their way out west. The three pilgrims bought land in Seattle in 1874. One son, a baby named James, did not survive their exodus, but two more children were born to the Taylors; Walter and Alice. Brother William married and moved on while Thomas, a ship carpenter, drowned at sea in 1890.[i] He left the two children with a respectable sum of money, $2,400 each.[ii] Emma and Alice supported each other on the inheritance and what Emma could pull in as a dressmaker, while Walter left for San Fransico and found work in a hotel.

1889, the Women’s Christian Temperance Society began a campaign, having learned of the impropriety of male officers who were permitted to search female prisoners. It was assumed that when a woman’s behavior was depraved enough to put her in that position, she wasn’t worth much.[iii] But times were changing. Washington had just become a state. Women were both discouraged and enraged over a series of injustices that resulted in gaining the right to vote and losing three times thus far. Emboldened by their organized numbers and the indignities their sex had endured, new battle lines were being drawn. If their brothers were not going to allow them in as citizens, they would find other means of influence. The women of Washington would be vigilant. Making sure that no man dare abuse their power over them.

The City of Seattle was in a period of rebirth. Not long after the settlement had become a city, a mishap at a woodworking shop that involved heating glue over a gasoline fire, set the tinder-ridden downtown ablaze. The entire business district, 25 city blocks, were reduced to ruin.[iv] Soon after, tents sprung up from the ashes where storefronts once stood. The city refused to slow or sacrifice a single day. While Seattle demonstrated its tenacity and resilience, Emma Taylor saw an opportunity for her own renewal. The Governor had signed the Matron bill into law in 1893 and immediately, Mayors and Police Commissioners in major Washington cities were scrambling to fill the required post. Mrs. Taylor had cultivated a friendship with an Officer Wallingford, who championed her over the other applicants. Emma Taylor was sworn in as Seattle’s first Police Matron in June of 1893.[v]

Not long after her appointment, Emma and Alice received news of Walter’s mysterious death. He had been found by authorities in San Francisco, unconscious in the street. He later died and his identity was confirmed as 19-year-old Walter Taylor. Emma and Alice were devastated and sought to have his remains delivered home, the circumstances of his death never resolved.[vi]

One Monday afternoon in February, 1897, Emma and Alice had gone shopping for ribbon on Pike street. Mrs. Taylor had taken their merchandise to the store counter, where she bought and paid for them. The clerk placed their things in a box which sat in wait while the two resumed browsing. Almost as soon as Mrs. Taylor had entered the shop, she clocked the movements of two young ladies who she considered to be “suspicious characters.” When Emma and Alice went to retrieve their purchases on the way out, the box was gone. Mrs. Taylor knew immediately who had taken it.

Mrs. Taylor followed the pair of young girls from shop to shop, watching as they made innocent, trivial purchases before absconding to a new location, the matron following close behind. Emma Taylor did not have an imposing presence – at only 5 feet 4 and 114 pounds. Had she cornered the young women, what then? What authority had she been given?

The job of matron varied from place to place. No uniform description of a matron’s position was provided by the state. Mrs. Taylor was tasked with taking charge of women and girls, be they a witness, suspect, or person in crisis, and see to it that they are safe and cared for;

“… the unfortunate classes of women and girls are brought to our attention, the intoxicated, immoral, depraved, neglected and despondent appeal to us for aid and receive our attention. Young girls at the brink of ruin must be reproved, advised, and governed, they require kindness, firmness and discretion.”[vii]

Mrs. Taylor lost her suspects in the crowd. She later returned to the department to verify with the acting Chief, who confirmed that she had the authority to make the arrest, the same as any of her male colleagues.[viii] But never in her career had her pay, nor the resources at her disposal, been equal to that of other officers.

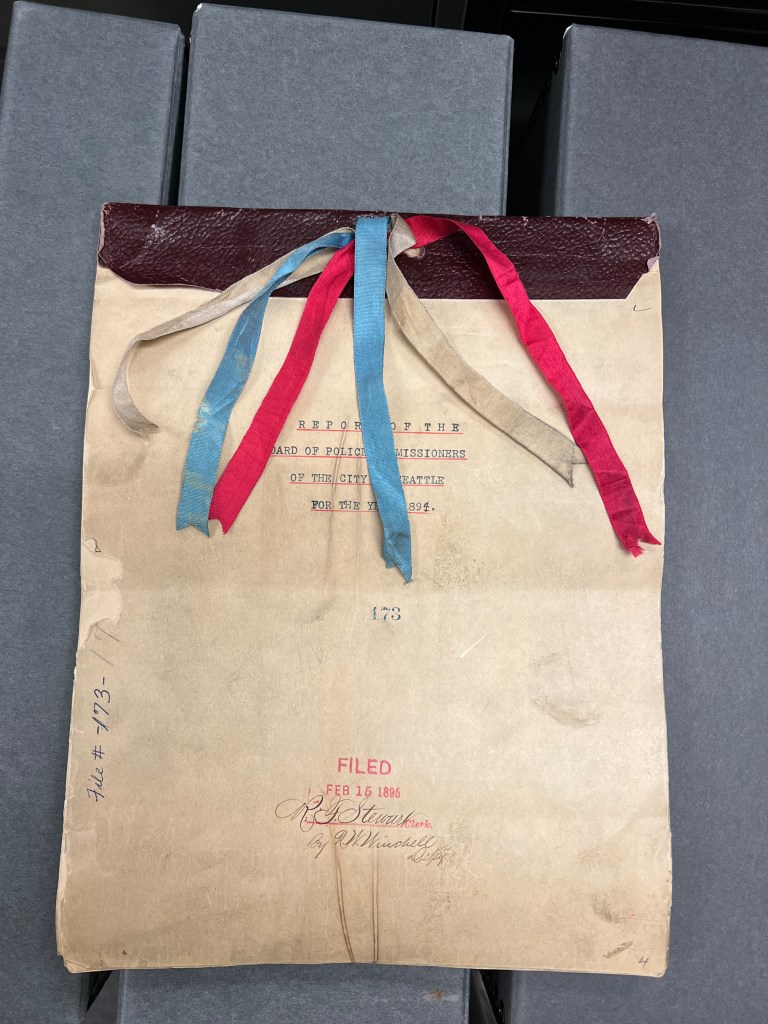

Annual police reports are catalogued at the King County Municipal Archives in downtown Seattle. Each packet lists numerically the various arrests, charges, occupations, and ethnicities of those who encountered the police. Three of the reports, 1894-1896 are bound together with the matron’s ribbons. Faded red, white, and blue in a knot at the top, bound one report like a crown. The year pf 1896 had a single, navy-blue ribbon in a bow. The report from 1895 is missing the ribbon, but contains a two-page insert. A Matron’s Report to the Chief of Police. Seemingly the first and last Matron Report that Emma Taylor was allowed to include. In it, Taylor conveys affection for the position and those who serve alongside her. Further on, a series of concerns were listed. Mrs. Taylor did not have transportation of her own, though she was “required frequently to go to different parts of the City and have so far been compelled to pay my own fare and that of others.”[ix] Her wages, $30 a month, were scarcely enough to cover her expenses, in addition to the needs of the women in her care.[x] On call twenty-four hours a day, Taylor was required to pay for the phone needed to call her to the station, usually in the middle of the night.[xi] She requested a room be dedicated to her at the jail, so she could “remain on site at all times and be able to respond promptly to any necessary call.”[xii]

Female prisoners were kept in separate cells at the jail, while others who required “safe keeping” were sent home with Mrs. Taylor. The 1890s bore witness to the effects of the worst depression to have impacted the United States thus far. Taylor discovered destitute families, whose unemployed husbands and fathers marched on Washington DC, leaving their sick and starving loved ones behind.[xiii] As Police Matron, Emma Taylor was the first social worker for the city of Seattle before social services existed.

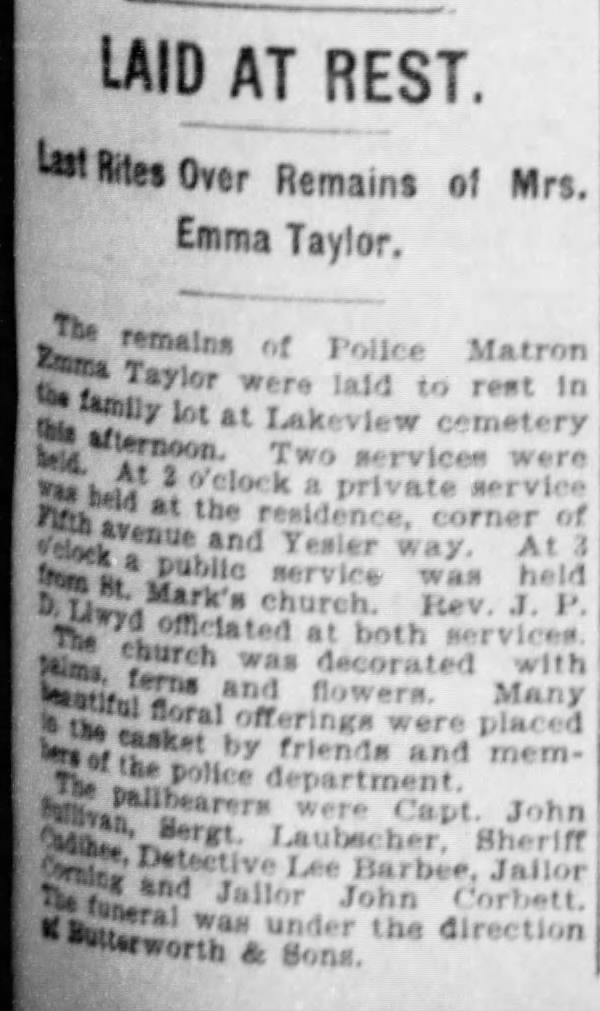

The implication in the absence of the matron’s report in subsequent years seems significant. Were her concerns addressed? To be the only matron in the entire city of Seattle, one would have to have an urgent sense of duty and concern for the safety of those she served. In her report, Mrs. Taylor conveyed as much, stating that “[They] appreciate that there is a woman to care for them.” The conditions and nature of the work left Emma Taylor physically and emotionally vulnerable. She served seven years as the sole matron of the Seattle police department. Due in part to the position’s demands, Emma Taylor died in her home at 5th and Yesler at the age of 53. Following Mrs. Taylor’s illness and death, two matrons were hired to replace her.

Women in these masculine spaces were, at once, elevated in what set their sex apart, while simultaneously degraded for how seemingly useless those differences made them. Elevated in purpose, yet isolated and under supported, the Matron was the precinct mother and mother to all women and girls in need. Expected to take all of it on with gratitude and love. Only she could do the job, but the job and the skills required were of less value in a profession that sought out and celebrated dominant male attributes. One Chief would hand her the reigns, while the next would feel compelled to reign her back in. Her jurisdiction was never allowed to intersect with that of her male colleagues, and when it did, she was an auxiliary participant, seldom receiving credit at all.

To be continued …

[i] King County, 1880 and 1900 Census, FamilySearch.org.

[ii] “Probate Department – Lichtenberg, J.” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Seattle, Washington) Sat, Aug 06, 1892, p 5.

[iii] “White Ribbon Work; Wide Scope of Woman’s Christian Temperance Movement,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 10, 1891, p. 5

[iv] “The Great Seattle Fire” https://content.lib.washington.edu/extras/seattle-fire.html

[v] “Sims Is Let Out” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Seattle, Washington), Sat, Jun 03, 1893, p 8.

[vi] “Delayed News of Son’s Death” Ibid, Thu, Aug 31, 1893, p 8.

[vii] “Matron’s Report to Chief of Police”, Annual Police Reports 1894-1930, General Files, Seattle Municipal Archives, December 31, 1896.

[viii] “The Role of Old Sleuth: Police Matron Taylor Played it on Monday to Perfection,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Feb 10, 1897, p. 8

[ix] Matron’s Report.

[x] Harriet U. Fish, Law Enforcement in Washington State (Bellevue: Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, 1989)

[xi] “She Will Escape — Police Matron Is Not Affected by the Civil Service Law,” The Seattle Times, April 24, 1896, p. 5.

[xii] Matron’s Report.

[xiii] “Coxeyites Starving Family” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Seattle, Washington), Fri, Aug 24, 1894, p 8.