Whidbey Island, Washington Territory

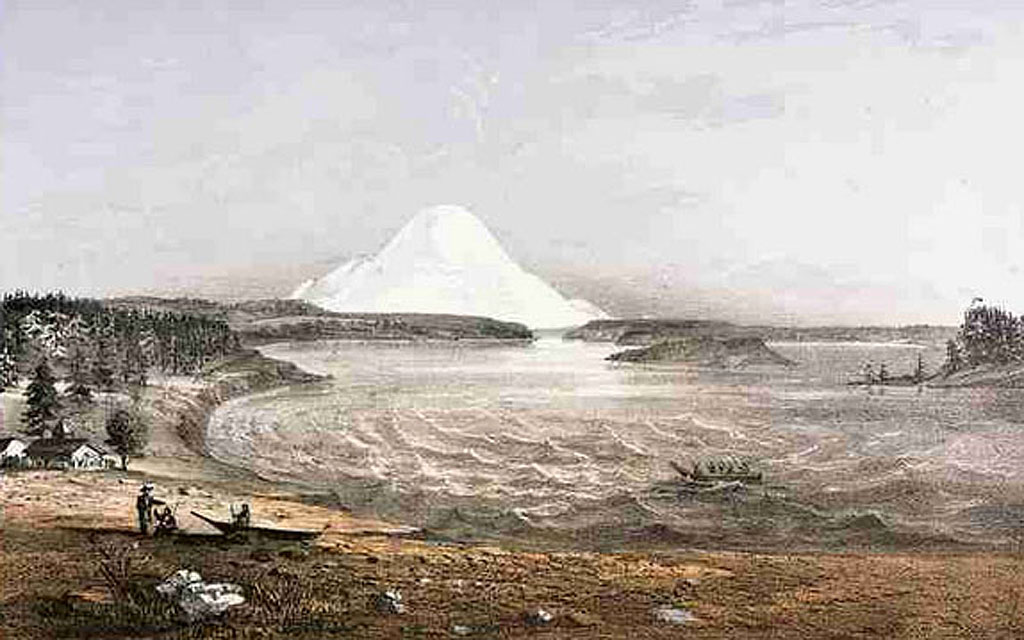

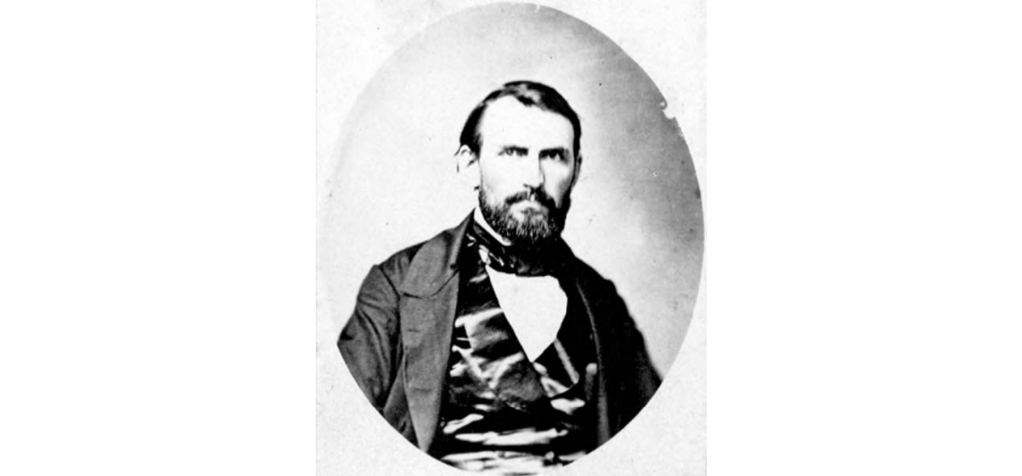

Like the god of a new world, Isaac Ebey stood on the shore of the settlement at the base of the Puget Sound. A great mountain range at the center of the peninsula beyond left him paralyzed, reverent. The dark tree line gave an impression of jagged teeth against the whiteness of the snow. The peaks seemed to hover above, dominating the skyline, reflected in the bay at his feet. That, he determined, was Mount Olympus. This town was to be named Olympia. The Colonel left the name behind, like signing his signature on the landscape itself, before he shoved off in his canoe. He had been summoned up sound by his friend, Samuel Crockett, who persisted in promising that the best land lay ahead. Whidbey Island was flat, fertile, and undisputed by other white men. Another wonder on which to stake his claim.

“My dear brother—

I scarcely know how I shall write or what I shall write . . . the great desire of heart is to get my own and father’s family to this country. I think it would be a great move. I have always thought so . . . To the north down along Admiralty Inlet . . . the cultivating land is generally found confined to the valleys of streams with the exception of Whidbey’s Island . . . which is almost a paradise of nature. Good land for cultivation is abundant on this island. I have taken a claim on it and am now living on the same in order to avail myself of the provisions of the Donation Law. If Rebecca, the children, and you all were here, I think I could live and die here content.”

POR2045

The Donation Land Law of the United States had disposed of the land, long cultivated by its original people, as if it were uninhabited. Yet 1500 Skagit resided in permanent villages.

Rebecca Ebey arrived from Missouri in 1852 with their two sons and her three brothers.

“All around seems beautifully adorned in quiet serenity. No bustling crowd as in a city or town to mar our peaceful happiness. Although we have not towering churches, yet we can spend our time in training the young minds of our children in the principles of Christianity and creating within them a thirst for moral knowledge…”

Rebecca Ebey became the first permanent white-woman settler on the island, but more would soon follow. She established a school and began educating children, including those belonging to the Skagit tribe. Though not necessarily content with their presence, the Skagit did not seem openly hostile. Perhaps they interpreted an advantage to embedding themselves among the white men with guns as they “might protect them from slaving and plundering raids by rapacious tribes from Canada.”

These white invaders could provide them protection. Despite the partnership that had developed on the island, the threat of failure loomed. Similarly fragile accords elsewhere in the region foreshadowed, that theirs would come to a violent conclusion.

The Tlingit people of Alaska controlled trade routes in the region. The people known as the Kake or the Dawn Tribe, were a matriarchal and proud people led by a woman warrior – the daughter of the slain chief.

The USS Massachusetts let loose a volley of cannon fire the morning of November 21, 1856. One hundred Tlingit warriors had stopped to camp on the shores of Port Gamble. No one bothered to ask what they were doing, or why they had come. The party had been spotted approaching Steilacoom at the southern end of the Sound. They alerted the fort nearby. Fort Steilacoom, roused its stagnate militia into action, but before they could materialize a response, the threat had migrated north. Word traveled on, accelerating the urgency and malicious intent as it spread up the coast.

The nearby lumber mill sounded the alarms that prompted the party to flee in their canoes, just as spheres of steel rained down from the sky. The barrage of shelling and small arms fire killed 29 and wounded roughly the same. Among the dead was the Tlingit chief. Survivors were rounded up, fished out of the water, and deposited back onto the Russian-American colony.

A ku.éex’ for the fallen was observed. The ceremony named the clan leader’s daughter as his successor. Charged with fulfilling the spiritual obligations to her people. Settling the affairs of her father, and restoring balance to the region and reuniting her people. Just as the eagle takes from the raven, and the raven reciprocates in kind – she would claim the life of the white tyee.

Dr. John Kellogg was the only white physician on Whidbey. He served the island as well as the surrounding port towns, earning him the moniker – “the canoe doctor”. He attended to Rebecca Ebey, who had given birth to a baby girl named Harriet before she died four months later, at age thirty. Col. Ebey remained in the home on the cliffs overlooking Penn Cove. He would remarry. A widow who would soon be widowed once more.

Dr. Kellogg was well known in Port Gamble, which is where he had gone on the night of the raid – unaware that it was his life that was sought in restitution. The Tlingit went house to house, asking after the whereabouts of the “white Tyee”. In absence of Kellogg, Col. Ebey was named as the highest ranking person on the island.

The war party surrounded the Ebey cabin by the sea. One of them fired a shot in the air. Col. Ebey opened the door to investigate –

Later that night, a neighboring family took refuge in home of Hill Harmon, telling him what they had heard and seen. Harmon armed himself before riding to Admiralty Head, alone on his horse. All had gone quiet. As he approached, he discovered a motionless heap laying in the doorway, dim lantern light from the house outlined from behind. As Harmon approached, he knelt to examine Ebey. He had been shot in the chest. His head had been severed from the body and removed. Harmon scoured the area to find it.

The sack rocked with the motion of the water, nodding – as if still animated in agreement. Justice called for his sacrifice, so that the balance of power in the region could be restored. The morbid trophy continued to nod as the party pushed home, unincumbered by naval guns or small arms fire from the shore. No retreat or need for alarm. The warrior had passed her pain on, in exchange for the head of the white chief. Her anger subsiding as the distance grew between their party and the island in their wake. Her pain was now there with them. Her power reinstated. That pain would become a story, the lesson for future generations. That power could not be challenged without consequence.

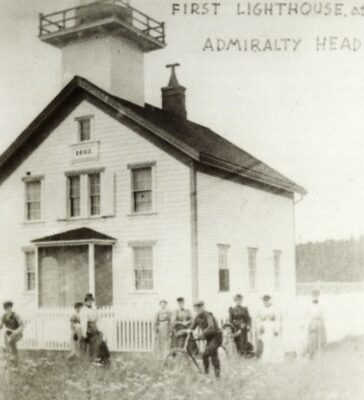

In an act of dominant defiance, the government constructed the Red Bluff Lighthouse near the site; a symbol like a steeple, or an obelisk marking Col. Isaac Ebey’s grave. Dr. Kellogg sold the land for $400 from the US Lighthouse Board in 1858. Caroline Kellogg insisted they move further inland, away from vulnerable shores.

The Pacific Northwest Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 claimed roughly 60% of the lives of the Tlingit people. Efforts to contain the spread, like quarantine and inoculation, were reserved for colonial settlements on either side of the boarder. The indigenous were abandoned. On the same page of the October edition of the Washington Standard newspaper, citizens of Olympia were cautioned to cease all intercourse with the indians, while two columns to the right, inviting the readership to embrace the vaccine that was “the greatest discovery of the age – a blessing to mankind“.

Sources:

Colonel Isaac Ebey, letter to his brother, W.S. Ebey, Olympia, Oregon, April 25, 1851, Winfield Scott Ebey papers, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.

Patrick McRoberts, “North Coast Indians, likely members of the Kake tribe of Tlingits, behead Isaac Ebey on August 11, 1857”, HistoryLink (Seattle, WA), 2003, https://www.historylink.org/file/5302.

Edmond Meany, History of the State of Washington. (Macmillan Company, 1909), pp. 205–206.

Rosita Worl, “The Tlingit People and Their Culture: Ceremony and Celebration” Smithsonian Learning Lab, p. 17, https://learninglab.si.edu/collections/the-tlingit-people-and-their-culture/.

Greg Lange, “Smallpox Epidemic of 1862 among Northwest Coast and Puget Sound Indians”, HistoryLink (Seattle, WA), 2003, https://www.historylink.org/File/5171.

“Notice”, The Washington Standard (Olympia, W.T.), October 4, 1862, p. 4.