I have on my laptop a simple reminder, written in pencil on a muted yellow stick note. Something I must remember in my approach to both past and present – People are complicated. In research, as in life, the first conclusion you come to is not always the correct one.

I attended my first writer’s conference in October of 2023, in preparation for writing my book. The first session was three hours long on a Friday afternoon. I had misread the agenda and arrived a half hour late. This was strike one.

The class was on nature writing. When it comes to the natural world, I am a tourist. I use nature as a necessary and temporary escape from my preferred, urban environment. Nature restores me and renews my appreciation of the moment, for quiet, and contemplation. I could not tell you about native plants, nor could I withstand too much nature. I attended that class to discover a new tool. Nature writing as a new way to convey human experience. There was much talk about the “nature” of man and woman in my research. I’d hoped to excavate the natural world for imagery and inspiration.

The woman, an author and professor, stood at the head of the classroom in the Edmonds Community Center. She was slight, the table top she leaned on behind her could have sliced her exactly in half. She had long, silky black hair that did not seem real. It sank down below her shoulders to almost her elbow, a blue baseball cap affixed to her head. Her hair looked strong and young, while her face was that of someone in her late 50s, early 60s. It must be a wig, I decided to myself, reserving no judgement. I had recently begun to lose more hair than usual, on account of stress and not taking better care of myself.

The woman read passages from books, including her own, that illustrated how scientists utilized narrative techniques to bring the natural world to life. I definitely signed up for the wrong class. I divided my attention between what was being said, the brainstorm brewing on the paper in front of me, and the children playing in the yard to our right, just outside the open windows that ran the length of the room. The woman was growing agitated, though she was good at concealing it. No one can hope to compete with pre-school children playing in the late afternoon sun, who have also discovered that they have a captive audience of middle-aged women.

The final hour had finally arrived. The children had been rounded up and sent inside. We were due to end early, having fully exhausted the topic and the presenter’s patience. She opened herself up to questions, and I, not wanting to declare the time a total loss, posed a question.

“Hi, yes … I am a history writer.” Strike two. “I have come across some accounts in my research, remembrances from early settlers, that described customs from the Skagit people on Whidbey Island – ” I went on, relating my desire to illustrate these indigenous practices, how they communed with nature, and before I could articulate more – she interrupted. I had struck out.

“History?!” Though surprised, she maintained a pleasant expression and tone in her voice. It would take me longer than usual to register her meaning in the words that followed. “You know what they say about history … lies agreed upon? History is fable.” She smiled as she turned her back to me and continued to the middle of the room. “You can’t write history as a science. These people, they are dead and buried beneath the ground. Their lives, their ways of doing things, those are gone too. You can’t observe or write about people who had their land, their lives stolen from them …” It was then I understood. We were no longer talking about nature writing.

No one spoke after that, besides the lecturer who thanked us and concluded the convention for the day. I began to leave; discouraged and confused. A fellow attendee stopped me on the way out the door to convey her support. History had merit, based on her experience. History meant everything to me. History was the lens I viewed the world through. That woman had the unfounded audacity to dismantle my perspective before a room of strangers. In a class I should have never attended in the first place, paid for with money I didn’t have.

I was furious. I drove home, running the scene over and over. My husband called, piped through the car’s Bluetooth, asking when I would be home. My mom and stepdad had flown in that morning, and he was eager to disappear. I could relate. I asked for permission to speak freely before I expelled the story from my brain. He asked some standard follow-up questions, as he always did. Advocate for the devil, that he was. I normally despised him for these intrusions of reason, but it was only then that I uncovered the clues. Forced to acknowledge what was likely the most plausible explanation for the woman’s response. I was immediately horrified.

Her surname was Raven. I noted this as I left, determined to remember it when it came time to evaluate the course. In her nonfiction writing, she had conversations with the animal main character. She invited us to entertain her claim that communication between humans and animals could be scientifically supported, which caused me to place a hand over my mouth to conceal a smile. Her reverence for nature was something I couldn’t understand. Even her hair was beyond me. The hair that could not have been real, may have been the hair of an indigenous woman. Had I come to the lecture on time, I might have learned more about her. Perhaps even understood why a question like the one I posed could be so problematic.

If there is anything I have learned in recent years, is how divisive the subject of history can be. It’s one of the reasons I am glad to not be teaching. The fault lines of history run beneath the foundation of my own family. History is personal. This is evident in the defensiveness elicited by unflattering portrayals of mythical men. Politicians who justify or outright deny the existence of painful, inconvenient narratives. Maybe she was right. Something so subjective could not be seen as credible. That science is the only way one could accurately measure the world around us.

But even science has a history. Our understanding of the natural world has grown and adapted to change over time. For me, personally, the aspects of history I love most are events that expose human progress. Growth in the face of challenges, whether natural or man-made. The study of history has to grow and adapt in order to survive. New narratives will continue to emerge. Challenges to pre-conceived notions will inevitable present themselves. If we are too precious with our stories; if history becomes too static, or too personal – it will not stand the test of time.

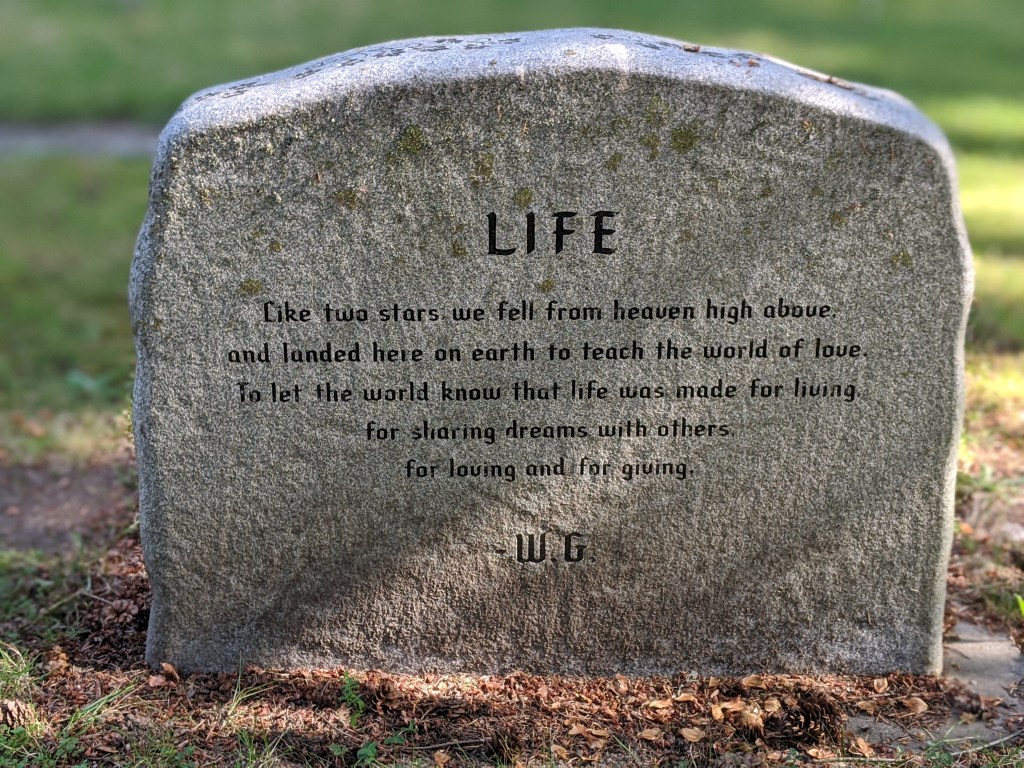

I look to my posterity to know my story, even more accurately than I do now. I trust them to know how to use it in whatever way serves them best. Our stories will all belong to history, informed by other’s perspectives, and whatever clues we might leave behind.

History is personal, and people are complicated. If there is anything I have learned in the process of living, it is that.